Our Neighborhood: Smoketown

How We Got Here

We decided to make Smoketown our new home in 2023 so we could be closer to the neighborhoods we serve. After purchasing and renovating office space on S Shelby St, we moved in March of 2024.

Along with getting us closer to the neighborhoods we serve, our new office has given us space for our team to grow. With a larger team, we can expand the work we do growing Louisville's tree canopy.

This new phase of TreesLouisville is only the beginning. In the future, we plan to continue investing in our new home on Shelby Street by adding a garage with dedicated offices for our Green Team staff. This expansion will help the Green Team further the work they do, planting and maintaining our trees to help ensure we have a large and healthy tree canopy for future Louisvillians.

Smoketown's History

Settled by freed African Americans following the American Civil War, Smoketown is Louisville's only neighborhood that has been home to free

African Americans since its inception. The name dates back to at least 1890. While its origins are not known for sure, most attribute it to the factories that used to inhabit the neighborhood, either because of the smoke that would billow from their chimneys, or their initial use as cigar factories and tobacco warehouses. Smoketown is sometimes referred to as Smoketown-Jackson, though the Jackson name came later as a rebranding effort by the city in the 1990's. Jackson was chosen as a reference to Jackson St, which runs through Smoketown.

The first public building in the neighborhood was the Eastern Colored School, and when it was built in 1874, it was one of the first public schools in Louisville where black children could attend. Unlike other places at time, the school also had black administrators.

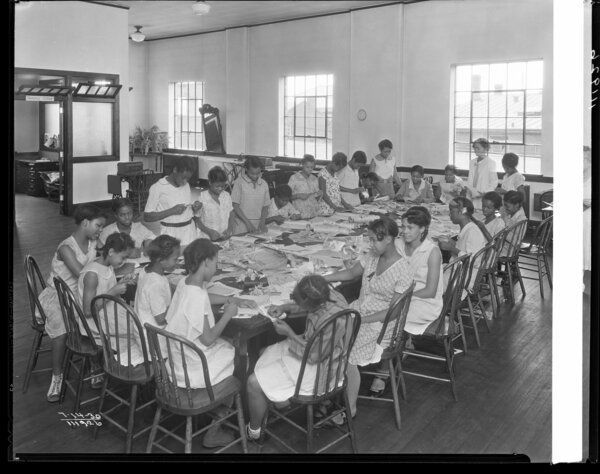

In order to provide vocational services and limited education to the black residents of Smoketown, the Presbyterian Colored Mission, later renamed the Presbyterian Community Center, was established in 1898. The mission helped provide vocational training for men, domestic training for women, and religious services on the weekends. The mission provided some benefits to residents, but it's impacts were limited due to its white funders racist belief that black people did not benefit from academic instruction.

The center survived until 2013, and over those year the services and image of the center changed, too. By the 1950s it offered youth sports leagues, including boxing. The center's boxing league in particular trained renowned boxers like Ruddell Stitch and Jimmy Ellis. Muhammad Ali also credited the center as the first place he learned to box.